|

ROBERTA MARGARET YOUNG "ROBBIE” MADDEN - CIVIL

RIGHTS AND FEMINIST ACTIVIST, ERA ORGANIZER, BREAST CANCER SURVIV0R

I was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa,

on the ninth of November 1936 and brought up in Ames, Iowa, right in the middle of America. I was the eldest of

four children, my sister Judy was a year younger, sister Sherry six years younger, and brother Charles Loren nine

years younger. I was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa,

on the ninth of November 1936 and brought up in Ames, Iowa, right in the middle of America. I was the eldest of

four children, my sister Judy was a year younger, sister Sherry six years younger, and brother Charles Loren nine

years younger.

I was a serious child and, as the eldest, was most aware of the precarious position of the family’s finances. My

father, an accountant, worked for the government during World War II. After the war he worked in various businesses,

never successfully. He was a poor provider and I remember a time when we didn’t have enough to eat. My parents

divorced when I was fifteen.

I was a young child when my mother took a job in Rushing's Supermarket. When I was twelve, she came home from work

one day and told us she had been passed over for the manager’s job in favor of a man who was younger and less qualified.

For the first time I felt outrage and became aware that some things are just dead wrong. I remember my mother saying,

“He was just a bag boy, that was all he did.” That instant marked my awareness of injustice. Even today I won’t

retire from activism until racism and sexism are eliminated.

Life seemed to go on as before in our two-story white house at 511 Lincoln Way after the divorce, but I had changed

significantly. I took a job in the supermarket that had discriminated against my mother and used my earnings to

buy books to improve myself.

This resulted in a scholarship to Iowa State Teachers College, encouraging a misguided attempt at becoming a schoolteacher.

In those days women became teachers or nurses, and I didn’t have the imagination to consider something else. Instead

of going into teaching I did something seemingly even more conservative by temporarily abandoning my education

to get married.

Jerry David Madden was fresh out of the army when we met. He was a writer, a radical thinker, and an exotic creature

in my world. Until I met him I was called Bobby, but I soon had a new nickname, Robbie, and I changed my surname

as well. Within a year we married.

My mother did not wholeheartedly support my choice of husband, considering Jerry Madden was a poet with no substantial

prospects. In the early years I worked to support my husband, who later taught at several colleges and universities.

In 1968 he was hired by Louisiana State University as an English professor, and we moved to Baton Rouge. There

I started my political career in earnest.

Our son Blake, born in 1960, remembers “When we moved to Baton Rouge, we had dinner with the landlord of our rented

house. A young teenage black man was working for the landlord-. The landlord sat us at his table, but had the young

man eat outside on the porch. My mom felt he did that because the helper was African American. I remember her crying

because of the situation. She never forgave the landlord and I doubt he could ever have done anything that would

change her mind."

Public speaking didn’t come naturally to me, and instances like these compelled me to speak out. I remember *Sally

Kempton saying, “It’s difficult to fight a battle when the enemy has outposts in your own head.” Brought up to

believe that women’s main role is to provide a home and children, I found the path of activism to be long and filled

with challenges.

Robbie with Lou Gossett at a

YWCA USA convention, where she received the One Imperative Award for her work on racial justice at the YWCA Greater

Baton Rouge. This was about 2005.

|

Books had been important in forming my political views; in particular, Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex awakened my realization that women didn’t have to take second place.

I went back to college in 1966 and graduated summa cum laude in Government from Ohio University in only two years.

In Baton Rouge in the late 1960s, I found a job as book editor at Louisiana State University Press, where I met

Maureen Hewitt, also a book editor. We became close friends at a time when the women's movement was sweeping the

nation. Together we founded a chapter of the National Organization for Women. Many of our early meetings were consciousness-raising

sessions. Sylvia Roberts, a feminist attorney who had successfully argued Weeks v. Southern Bell, became our mentor.

Maureen and I participated in national NOW meetings. Locally, we worked to change discriminatory credit laws and

to focus attention on the sexism in children's books (boys can be firemen; girls can be nurses). “Robbie preferred

being in the background," says her friend Maureen. "So she persuaded me to be president of our newly

founded Baton Rouge chapter of the National Organization for Women. Robbie served as vice president from 1972 to

'75.”

I became an active member of Women in Politics, precursor of the National Women's Political Caucus. The organization

eventually died out, but I started it again in the 1990s, and at one time we had 300 members. However, we could

not sustain it, and the organization is no longer active in Louisiana.

Blake remembers as a teenager coming home to find NOW meetings being held in the living room. “I saw Mom was actively

involved in making changes that have helped women and minorities,” he recalls.

In 1979 I ran for state Senate as a Democratic candidate. My campaign news release read, “The needs of older citizens,

especially those on fixed incomes, deserve special attention. Government ought to be more accessible to the people,

and voter registration must be opened up to make it easier and simpler. Louisiana’s education system should be

strengthened by supporting and better evaluating our teachers. Parents want to be and must be more actively involved

in the schools. Environmental problems must be solved before Louisiana’s natural beauty and wholesome environment

are lost forever. Voters have a right to expect equitable treatment for everyone, rather than government by special

interest group.”

I lost the race to the incumbent but got a third of the vote with a campaign budget of only $35,000. I know that

my efforts had a positive impact on the people of the Senate district. Again, another consciousness-raising moment.

I was once asked when I presented information, “Who wrote this for you, sugar?” It was difficult to be taken seriously

as a candidate by most men.

I gave up a political career and turned my energies to working for several nonprofit organizations, including the

American Diabetes Association, Common Cause, and the Baton Rouge Consumer Protection Center, and I volunteered

on countless committees and community projects.

My most enduring commitment outside of my marriage has been my eighteen years at the YWCA Greater Baton Rouge.

Eliminating racism and empowering women is the YWCA’s mission and mirrors my own personal mission. As Director

of Public Policy and Women’s Health, I created the ENCOREplus breast health program, which helped low-income women

get free breast and cervical screenings. With Maxine Crump, I helped design the highly successful Dialogue on Race

program, and as Director of Racial and Social Justice, I established it as a major program, later adopted by other

YWCAs. I also created other events dealing with racial and social justice for the YWCA and the community.

In 1993 I was diagnosed with breast cancer. My treatment was a lumpectomy to remove the malignancy and radiation

to stop it from coming back. This experience served as motivation for my later work on breast cancer awareness.

I'd thought my diagnosis was a death sentence, but soon learned that early detection meant a good chance of survival.

Researching my condition, I found that black women were more likely to die from breast cancer even though the incidence

of the disease was higher in white women. Late detection is one of the factors that contribute to this disparity.

My lump was found early due to my regular self-checks.

On Mother’s Day 1995, I launched the YWCA Greater Baton Rouge ENCORE plus program to raise awareness of breast

and cervical cancer. The program targets African American women who more often don’t have insurance or may not

be aware that they need regular mammograms and Pap smears to check for breast and cervical cancer, but helps all

women who need the service.

THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT (ERA), first proposed in 1923, has a straightforward goal: to

ensure that equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States government or

by any state on account of sex. I'd already spent a decade working to have the amendment passed in Louisiana and

in 2004 I again took up the challenge and helped to organize the Louisiana ERA Coalition. The group has lobbied

and testified for the ERA twice in recent years; both times it was defeated in committee.

* Sally Kempton, a journalist and early radical feminist left public life early on and became a nun and follower

of the late guru Muktananda.

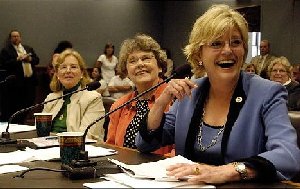

Robbie (middle) testifying for

the ERA with State Rep. Monica Walker (right), lead author for ratifying the ERA in Louisiana in 2007.

|

FAST FORWARD

Last year Robbie and her husband moved to North Carolina . Retired from the YWCA, she immediately began whipping

things up in her new hometown, organizing an ERA activist group and a forum and dialogues on race. Her dedication

was noticed by the High Country Press, MAY 27, 2010 ISSUE. Excerpts from article writtenfollow:

MAY 27, 2010 ISSUE

Workers Needed for Equal Rights Amendment Ratification

North Carolina One of Three States Left to Ratify

Story by Bernadette Cahill

Iowa-born Madden lived in Boone more than 40 years ago when her husband, author David Madden, taught at the Appalachian

State Teachers College, now ASU. She was in town last week initiating a hunt for local supporters to work on ratification.

She began the process in Black Mountain when she moved from Louisiana six months ago. Boone was the first stop

on an evolving statewide trail.

The ERA, first introduced in Congress in 1923, was approved by the House in 1971 and the Senate in 1972, with a

seven-year deadline on ratification. The deadline was later extended to 10 years, but the ERA stopped three states

short of ratification in 1982. It has been introduced in every session of Congress, except the current session.

Madden’s plan is to establish a network of individuals in each of North Carolina’s 120 state electoral districts;

the individuals would lobby their district’s representative regularly about ratifying the ERA.

“Women are not included in the Constitution except for the right to vote. That is the only protection they have.

They don’t have the protection that minorities have,” said Madden, stating why it is important to have the ERA

ratified.

“For every legislative battle we have to start all over again.”

The Three-State Strategy

Robbie at the MLK march in Baton

Rouge in 2005. She is first from left behind the YWCA banner.

|

When the ERA failed ratification in 1982, it was believed the amendment was dead and the process would have to

begin again. But in 1992, a major development occurred that may have resurrected the original ERA. That year, the

Madison Amendment concerning congressional pay raises passed ratification after 203 years, reported the ERA campaign

website www.eracampaign.net.

This 27th Amendment’s incorporation into the Constitution has raised the possibility of the continuing viability

of the ERA, especially as mention of a deadline is not included in the text of the amendment.

ERA supporters have adopted what is known as the “three-state strategy,” an attempt to have three more states ratify

the amendment and challenge the deadline. Madden’s proposed network to lobby for ratification in North Carolina

is part of this three-state strategy.

The ERA would be “the bedrock” in the Constitution that equal rights litigants could point to for redress and if

it went to the Supreme Court, “they will win,” she said.

Comments to Jacqui Ceballos: jcvfa@aol.com

Back to VFA Fabulous Feminists

Table of Contents |

|