| MERRILLEE A. DOLAN EARLY NEW MEXICO ACTIVIST  I was born in Durango, Colorado, to Cheryl Berry and Robert (Bud) Minton on October 11, 1941. Soon thereafter, my parents moved to Los Angeles, where my father began attacking my mother and me. My mother started assembling bombers at Douglas Aircraft, leaving me with Memaw, my father's mother. I contracted polio but recovered. Before I was old enough to walk, Memaw took me to live with my father's sister and her husband in Grand Junction, Colorado. Both my aunt and uncle worked, and Memaw often left me with a teenage boy who molested me. Subconscious memories of these acts resulted in shame, self-loathing, and suicidal thoughts that lasted into my thirties. Grandmother and grandfather Berry, who lived in Durango, returned me to my mother in Los Angeles, but my father became even more violent. One night my mother had a powerful dream: Take Merrillee and leave! and we fled home to Durango in my grandparents' car. Nightmares of a man chasing me lasted for decades. My mother filed for divorce and started working at the First National Bank. She and grandmother transformed our yard into a showcase in Durango, and my mother hosted a Saturday morning garden show on the radio. On Saturday afternoons, she would take my friend Linda and me hiking up the trail on Reservoir Hill and teach us about the spiders, lizards, and flowers we saw. Her love of horticulture rubbed off on me, and I minored in botany in college. My grandmother was a magnificent woman. As district supervisor of a Works Project Administration program for southern Colorado counties, she established the first child-care centers. She sewed for me, read to me, and helped with school projects. With just a high school education, she knew Latin, algebra, and geometry. My mother was happy while single, but in June 1952, she married John Dolan, a Durango High School acquaintance home on military leave. John's opinion of females opened my eyes to the ugly reality of misogyny. John was an alcoholic and an abuser. Military families move often. In six years we would move six times and live in three states. I would attend five different schools. John was stationed in Fort Benning, Georgia, and we spent most of that first year in Columbus, Georgia, in a shabby white house across from railroad tracks. The temperature rose to 100 degrees, and the humidity hovered at 99 percent. We lacked even a fan. I started the sixth grade at Tillinghearst School and made friends quickly. Although I had plodded along in Durango, a demanding teacher motivated me to do better than I'd ever realized possible. In the spring of 1953, we moved into a tidy brick apartment in a well-manicured military complex at Fort Benning. During this time, my mother began turning against me, isolating me. A typical abuser, John caused dissention. I finished my sixth grade in the desegregated school at Fort Benning and completed the seventh and most of the eighth grades there. We military kids spent summers swimming, attending matinees, and exploring the dense woods. It was fun, but at home life was miserable. I was unwelcome in the TV room with John and my mother. When I was 13, John adopted me, and I thought he might like me better but he didn't. When not a sloppy drunk, John was mean and would stride through the house proclaiming, "I wear the pants around here!" One day, he gave my little dog, Flippers, away and I broke down crying at school. I had never felt so alone. A tightwad, John gave me no spending money. What I had, I earned by babysitting. My grandmother became my lifeline, sending me school clothes and a portable sewing machine. When I learned that my mother was pregnant, I felt sick. Now we were locked into this madhouse. The baby, a boy, struggled to survive, but he triumphed, and I bonded with him. I felt helpless because I couldn't protect him from John's constant rages. John was transferred to Greenville, South Carolina, when I was in the eighth grade. I spent the last two school months at Greenville Junior High, but we moved again to a different neighborhood during that summer. After ninth grade, in early June, a friend and I got jobs downtown working twelve-hour days in a discount department store. I was in heaven, having fun and making 55 cents an hour. My mother had another baby, a girl. Meanwhile, John kept drinking and lecturing that some wives deserved to be "disciplined" by their husbands. We moved to Waco, Texas, the summer before I entered the eleventh grade, our fifth move in six years-my last with this family. Hillcrest Hospital was hiring nurses aids, and John had said he wouldn't give me school bus money, so I earned it myself. I worked a 20-hour week from 4 to 8 p.m. after school and then walked twelve blocks home. I no longer ate at home and was there only to study. When John got a transfer to Denmark, I moved to Durango to live with my grandmother and attend Fort Lewis junior college. John later had a heart attack and the family retired to northern California. My mother ordered me to quit college and move near them. But with grandmother's backing, I refused and got the education my mother didn't value, attending the University of New Mexico, the Universidad de las Américas

I'd been seething over things I'd experienced because of my sex: job discrimination, limited career choices, a date rape, and pressure to get married. I'd gone to Júarez for an abortion, illegal in the United States. I'd been scolded by a Catholic doctor when I asked for birth control pills, and I'd sat through a lecture by sexist lawyer F. Lee Bailey mocking rape victims. So in 1967, while in grad school at the University of Nevada in Reno, I joined NOW. I'd learned about NOW from an article in the Christian Science Monitor, which said that NOW was formed to bring women into full participation in society, to end job discrimination, and to change abortion laws. Although no address was given, founders were named: Katherine Clarenbach was a professor at the University of Wisconsin. I ran to the library to get her school's address and shot a letter off to her. After a couple of months, a return letter arrived with NOW applications. My boyfriend and I paid our dues. I had read The Feminine Mystique and knew about pay inequities because I had spent the past summer in a New Mexico government internship where I read the 1965 Handbook of Women Workers, which showed huge disparity in male-female wages in every job category. When I'd searched for other books on the status of women, all I found was Modern Woman, The Lost Sex (1942), which argued that feminists needed to have babies to overcome the neuroses of having no penis and wanting equality. I returned to Albuquerque and by the summer of 1968, finished course work for an MA in political science, campaigned for Eugene McCarthy, and learned there was a NOW chapter in Albuquerque. I'd been elected a delegate to the state Democratic convention in June. New Mexico's McCarthy supporters, up against party machinery, had the largest voting block of any non-primary state, and yet when it came to selecting delegates to the national convention, women were passed over. I was disgusted with the entire party. I attended a NOW meeting at which Tom Robles, director of the new EEOC area office, spoke about Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. I'd just experienced horrific sex discrimination by an employment agency that advertised a city planner job in the paper under "Jobs Either Sex." Yet when I applied at the agency, I had to enter through a separate door for Females, and I got a "females only" application specific to clerical skills. I was pushed into a filing job. After I told my story, Mr. Robles said, "Merrillee, I want you to file a charge." He invited me to apply for a state investigator job that his federal agency was funding to establish affirmative action programs with New Mexico employers. I started my state job in October 1968.

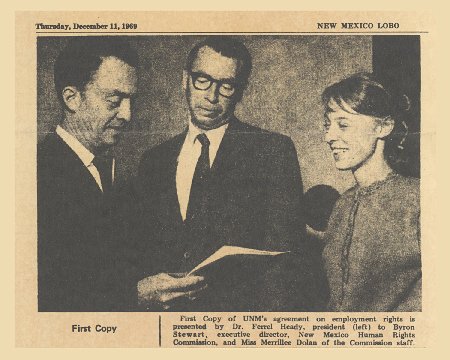

The affirmative action project manager and I traveled around New Mexico to persuade the 25 largest employers to advertise job openings (instead of hiring friends) so minorities and females could apply. You'd have thought we were asking them to perform unspeakable acts, the way they stonewalled and clenched their jaws. Now I had the money to fly to Atlanta for NOW's national conference, where I met Jacqui Ceballos (we served together on the national board for several years). What a thrill to meet Betty Friedan! I joined Betty, Jacqui, Dolores Alexander, Karen DeCrow, Muriel Fox, Lana Clarke Phalen, and other fantastic women for breakfast. They (and a few brothers) set in motion the changes that are today happening across the globe. My first demonstration was "Rights, Not Roses for Mother" on Mother's Day, May 12, 1969, in Albuquerque, part of a nationwide action. One day 18-year-old Yvonne Maestas, who was groped by her boss at a clothing store, came to my office for help. I rounded up NOW members and women's liberation members who demonstrated with Yvonne in front of the business. Manuel the Molester was FIRED! Using "Little Stinker Perfume," we tried to stink out a violent "art" movie that portrayed a woman being raped and murdered, and we organized a protest at a Bridal Fair. Four women were arrested, giving NOW a lot of publicity. We picketed the jail every night and all charges against us were dropped. We managed to get a liberal abortion law in New Mexico thanks to Los Alamos State Senator Sterling Black, who wrote and introduced a bill allowing abortions based on mental or physical health. Women fought for a state Equal Rights Amendment and got it. After Betty appointed me to head the Women in Poverty task force, I began publishing the newsletter "Sisters in Poverty." NOW chapters in various states worked with low-income women on issues that affected them. We supported striking Farah garment workers with pamphlets and articles. The AFL-CIO later supported us in our national fight for the ERA.

In Albuquerque we formed coalitions with Welfare Rights and with the Black Berets, a Chicano civil rights group. We walked hand-in-hand with them opposing police brutality. In the early 1970s, we had meetings, press conferences, and actions every evening and on weekends. We labored hours at mimeograph machines, printing materials typed on IBM typewriters. Women's groups got an ERA passed by the state legislature and two years later fought off an attempt to repeal it. When State Senator Eddie Barboa, who had introduced the bill to repeal, announced during a packed session at the legislature, "My wife wants to be liberated, and my mistress wants to be domesticated," Equal rights supporters and opponents alike were stunned into silence, and then hisses rose from the chambers. A caravan of cars drove back to Albuquerque that afternoon in a near white-out blizzard. Everyone--professors, businesswomen, NOW members and League of Women Voters-was happy. The only unhappy ones were Barboa (later sent to prison) and the church women who had been bussed in to testify that Eve came from under Adam's armpit, and, therefore, we didn't need an ERA. (UNM economics professor David Hamilton labeled it the "Right Guard Theory of Creation.") Women lobbied and got a Commission on the Status of Women, which was funded until the (female) Republican governor defunded it in 2011. At a February 1972 national NOW board meeting in Albuquerque, low-income women attended a speakout during which they described the frustrations of coping with welfare, making a living in a male-dominated society, and getting help for developmentally disabled children. I visited feminists groups in Denver, Salt Lake City, Norman (Oklahoma), Durango, and college towns in New Mexico. I addressed church groups, men's clubs and antiwar rallies where I spoke of war and the masculine mystique, thanks to Lucy Komisar's dynamite article titled "Violence and the Masculine Mystique." By NOW's fifth conference held in Los Angeles, excitement filled the air--we were unstoppable. Lynn Tabb of Riverside, California, and I got several resolutions for women in poverty passed. By the time of the Houston Conference in 1977, I had decided to make a big change in my life if I could but get a resolution to establish a national office to address the issues of women in poverty. Tish Sommers let me attach an amendment to her older women resolution; it passed, and I came home tired but happy. After that, I backed off from my activism, hoping others would pick up the torch. We accomplished a great deal during my activist years. Today, all over the world, the worm is turning for the benefit of women. Comments ro Jacqui Ceballos jcvfa@aol.com Return to Fabulous Feminists Table of Contents |

.jpg)