|

MAURA McNIEL

It is difficult to remember the day I knew I was a feminist because all of my life, I was involved in cutting-edge-of-change issues. My first conscious “aha” moment came in May 1971 when I attended a meeting in Ann Chud’s living room in Dallas, Texas, where a group of 14 had been invited to talk about our lives, our needs, our restrictions and what we could do about them. Ann had told us: “Once a year SMU gives us a feast with its Symposium on the Education of Women for Social and Political Leadership, but the rest of the year we starve.” So, how could we make the banquet last all year? The Symposium had been created by SMU’s Dean of Women Emmie Baine at the request of President Willis Tate “to do something special for women” as a part of the celebration of its fiftieth anniversary. He did not know what he was unleashing. In 1966 Dean Baine assembled a group of leading women of the area to help her determine what women most needed. The result was the first Symposium that brought to the SMU campus leading thinkers from throughout the country in a two-day event that mixed students, community leaders and Symposium keynoters in discussions to explore the role of women. It was, indeed, an intellectual feast. So it was that on that balmy spring night in May 1971 as I made way to the Dallas meeting that I had no idea that my life, as I was living it, was about to change forever.

Judge Sarah Hughes took over. Barely five feet tall and maybe was 100 pounds, Judge Hughes a formidable presence in the community, and she had zero patience for meaningless palaver. “You all get your act together,” she said. “Decide on your main concerns. Find a leader for each issue. After that we’ll meet again to determine how to proceed.” She turned to me. “Maura,” she said, “ you will be President. You are not working, so you have the time…and you get things done.” Then she turned to Sandy Tinkham, handed her a pencil and said, “Sandy, you will be Secretary because you take good notes. Any questions?” There was a moment of shocked silence before the room burst into spontaneous applause. That’s how I became the leader of the feminist movement in Dallas. How well was I prepared for the assignment? Not very. But I did have some organizational skills that had been honed a couple of years earlier when I participated in the first Explore program in Dallas. Created by women—Jean Swenson, Gail Smith, Jeannette Ivy, Mary Vogelson and Fran McElvaney—at NorthHaven United Methodist Church, Explore was a three-hour, once-a-week for eight sessions that challenged women to explore possibilities for their lives beyond the tradition role of wife/mother/homemaker. Classes were limited to 24 and taught by professionals who trained themselves and then taught others. At the very first meeting, we were told to introduce ourselves without referring to husband, children, parents or siblings. Some of us had nothing to say. I was one of them! The experience gave me expanded direction for my own life and I remained on staff for two years helping to teach others. Many times for the next year or so after I was “anointed” leader of this new women’s group, I wondered what had hit me.

It was only a year after women got the right to vote, and grew up during the Great Depression. My parents were second generation Scandinavian, my father, Oliver William Anderson and his family from Norway in 1870, and my mother, Hazel Anderson Anderson and her family from Sweden in 1850. I am the oldest of their four children. My brother, Harley, was born in 1925; my brother, John, in 1928, and my sister, Gretchen in 1936. We had an idyllic childhood, though we did not recognize it as such until much later when the travails of life produced experiences of comparison.

I am so grateful to my parents for teaching me that all people are worthwhile and should be treated with dignity and am grateful that they practiced inclusion. I did not recognize that others focused on differences where my family found community. One day the U.S Government came to our area, took our Native American friends and shipped them off to “Indian” Territories. My grandfather did everything he could to recover them, but to no avail, and it was very sad for all of us. High school for me was wonderful. I was on the staff of the yearbook, a tennis tournament winner and, among other things, the lead opposite Harry Reasoner in our senior play. Yes, the same Harry Reasoner who would say, following the launch of Ms Magazine, that after six months those women rebels would have nothing else to say. I enrolled in the University of Minnesota in 1939 and graduated three years later, cum laude, with a double major—English and Psychology. I had been rush captain of my sorority, Kappa Alpha Theta, and was tapped to Mortar Board. And I had studied with some of the country’s most outstanding professors, among them B. F. Skinner, Buckminster Fuller and Robert Oppenheimer. Our world crashed and our Eden ended on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and we were catapulted into World War II. Overnight, many male classmates signed up for the military. After graduation, I signed up for an engineering drafting degree at the Minnesota Museum of Art, planning to go to work for the war effort at Norden Bombsite. When I was not immediately hired after completing my drafting degree, I took an interim job at Donaldson’s Department Store. A friend and I became the creative artists, designing the store’s windows. We lifted those heavy mannequins, designed and dressed 16 display windows, we designed the in-store displays - not once but again and again. In addition, we planned and emceed style shows—all for $30 a week! We had an in-store intercom for emergencies, and I persuaded the president to let me do a half hour show of music and information every morning. I loved it! I wrote the script during my lunch break, and my pay envelope contained an extra $5.00 a week! The city of Minneapolis opened entertainment centers for men in the military. It was there I met Richard Crouch Arbuckle Jr., a tall, gorgeous Marine Corps officer. He danced divinely and played tennis like a pro. What more could anyone ask for in a husband? We were married on December 28, 1943. But the marriage was a disaster, not to be saved by the birth of my son Rick in 1945, so I took my son and moved home. Even while my parents welcomed me and exulted over their grandson, I knew I had no time to feel sorry for myself. I was a single mom with a child to support. For the first few weeks I wrote, putting all my frustrations, anger and uncertainty into a novel I called “Quicksand.” When the first and only publisher I approached turned it down, I tore it up and burned it. It had been good therapy, so it had served its purpose. My mom and I used to make a lot of my clothes. When I learned that Perry Brown, a dress manufacturer, might be going out of business, I went in to buy fabrics and zippers. They knew that I had done some modeling and asked me to try on a dress for a customer and I did. When she left, I went back to the owner and asked if I could comment, and gave him several blunt ideas on how to improve the dress. The designer overheard and was irate. She walked out slamming the door so hard the glass broke, saying “You do it then! I quit!” There was a market coming up, the owners’ last hope to rescue the business. I felt terrible and responsible, so I found myself offering to do their line. I did, and they helped me a lot, especially cutting and sewing. I was inspired and the clothes sold very well. That got me noticed as a designer. I have a large envelope of designs, clippings and ads that I saved, and the clothes would still be good today. After two successful years there at Perry Brown, I was recruited by Donovan Manufacturing Company, which billed itself as the leading Dallas fashion house. There a young associate, recently graduated from West Point to improve operations, interviewed me. His name was Tom McNiel. The initial interview went so well that he all but offered me a job. Then he took me out to dinner. The next day he sent me a note with flowers. The next day he took me to lunch, offered me the job of head designer and explained that he did not date his employees! True to his word, Tom McNiel did not date his employees; after I started working there, he resigned from his job and courted me relentlessly. We were married February 1, 1953, and there followed some wonderful years. I was in love with everything. I had three children in three and a half years—Bridget on February 3, 1955; Andrea on November 29, 1956, and Amy on July 19, 1959. Amy was born with profound Down’s syndrome and institutionalized at birth. The experts told us her life expectancy was a few months to at most three years; she died in 2015 at the age of 55. In 1961, after a long day skiing in Vermont, I went out for “one more run” after dinner and shattered my leg. I was hospitalized for weeks, with a hip-to-toe cast, with the possibility of never walking again – and a teenager and two small children at home. With lots of physical therapy and continuous exercise, I did walk again. But the injuries and poor healing have continued to plague me throughout my life, causing other issues with my bones and walking, so today while I enjoy great health in most all ways, walking is more and more difficult for me these days. As a wife, I followed the prescribed role for married women in the 1950s. We entertained constantly; I cannot remember how many dinner parties I planned, cooked, served and hosted, both to advance the career of my husband and because I was determined that our family knew our neighbors and our community. As a mother, I opened the world to my children, took them everywhere. I was a Cub Scout and Campfire Girls leader, a PTA officer, and the High School Sunday School teacher at Midway Hills Christian Church for 10 years during the turmoil of the 1960s. As a community volunteer, I dived into every evolving cause—the Civil Rights Movement, environmental issues, and neighborhood enrichment projects. I served on the boards of the Dallas Council of World Affairs, Pan American Round Table, the National Council of Christians and Jews, Common Cause and KERA-TV. I was a founder of Block Partnership and Save Open Spaces. At parties, I began almost every expression with “Tom thinks….” Then came the awakening! Explore, SMU’s Symposium. The meeting at Ann Chud’s house. I have not been the same since. I took the assignment that Judge Hughes had given me to be President very seriously, and slept only fitfully that night as I began to comprehend what lay ahead of me and how I would handle it. I spent the next two weeks exploring possible leaders for each task force. I was astonished at the expertise of possible leaders and amazed that not a single person turned me down. On August 17, 1971, I invited all the task force leaders and any of their team to my house for a meeting. We expected about 30 or so and it was closer to 70 spilling over in my house. Even Judge Sarah Hughes came, and sat at the head of our long dining room table. I sat across from Eddie Bernice Johnson, who said she was thinking of running for the Texas legislature. I just burst out like I do and said “Eddie you are black and a woman, you will never get elected.” She said she wanted to try. Judge Hughes said “Go for it.” I said “You, as a nurse, have such a good job at the VA. Be sure you get it in writing you can come back to the same position when this is over. But good wishes.” (She was elected, and is still in the U.S. Congress even today in 2015). We settled on the 9 task groups and the name Women for Change. We would begin our work to advance women with nine task forces: (1) Child Care, (2) Counseling, (3) Education, early; (4) Education, advanced, (5) Employment, (6) Legal, (7) Media, (8) Political, (9) Office location. We decided to plan for a big general meeting in the fall. Everyone seemed excited and ready for action. These were the nine Task Forces and their leaders: Dr. Flo Wiedemann, a psychologist, headed counseling; Esther Lipshy chose child care; Higher Education was headed by Dr. Barbara Reagan, an SMU professor; Lower grade Education, by Dr. Sonya Bemporad, director of the Dallas Day Care Association; Employment by Peggy Gue and Trudy Shay, both of whom had personally experienced discrimination at their work; Legal by Attorney Sue Goolsby; Media by Dr. Elizabeth Almquist, teacher/activist in communications; Public Relations by Dr. Mary Ann Allan, professor and social activist, and Space Search by Dr. Carolyn Galerstein, professor at the University of Texas at Dallas. On October 15, 1971, we had all of our background information organized and had secured the auditorium in Umphrey Lee Student Center at Southern Methodist University for our official founders meeting. The Dallas Times Herald had published a story, together with a coupon, inviting anyone interested to attend. The responses overflowed expectations. Three hundred and fifty women showed up for the meeting. Our Dallas audience was augmented with guests from Austin, Houston, Fort Worth and other Texas cities. Judge Hughes gave the keynote speech, explaining the need and the mission. I followed with an outline of what we had already done, explaining that we had, for their approval, chosen a name and had selected task areas in which to begin our work. I gave them a list, then sent them in groups of 25, each with a leader, to separate rooms at the University to discuss what they had heard and make recommendations. After an hour they returned. Transformed! Before the meeting disbanded, 300 had signed up and paid dues to become members. Within a few weeks, the space search task force had found us offices in the new Zale building. We began our work twofold: With women who needed help, and with companies that were legally obligated to comply with the 1971 Presidential Order for Affirmative Action, but needed help in responding to the law. We had longer and longer board meetings on Saturdays as the organization expanded and our responsibilities increased. Very soon our lofty goals of research and education gave way to crisis management. For the first few months we were open, most every call I answered at the office was from a woman who had been raped or beaten. I called members and personal friends to help. We were often told by women that when they reported the crime to the police, the interrogation was almost as bad as the rape. We were amazed at the seriousness of the problems so many women were having. I was so consumed with crises that there was little time to think and evaluate.

We worked diligently for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and were proud that Texas was one of the first states to vote for its passage in 1972. We supported two of our Texas sisters, Linda Coffee from Dallas and Sarah Weddington from Austin, who brought Roe v Wade to the Supreme Court. The “Wade” in the famous lawsuit was Henry Wade, the Dallas District Attorney. Many women in Dallas had been working to find a pregnant woman who could be the plaintiff to challenge the abortion prohibition in Texas, and found the woman we know as “Jane Roe” living in Dallas. Virginia Whitehill went with the lawyers to the Supreme Court in February 1973, and the gatekeepers tried to prevent the attorneys Sarah and Linda from entering the court because they were assumed to be secretaries. In a landmark decision about privacy, these young ladies won the case to make abortion legal in all 50 states. I remember that day in Dallas reporters asked me what I thought of the decision. I could gratefully say, “No more back alley tragedies. And this most difficult and painful decision is where it ought to be – with a woman, her doctor, and her family”. More than 40 years later we continue to debate this in the country. I still believe women need to control their own bodies, and men are still seeking to control women. We encouraged our friends to run for public office and were thrilled to support early winners Ann Richards for governor, Annette Strauss for mayor, Harriette Ehrhardt for state representative, Eddie Bernice Johnson for the state representative, and later for the U. S. House of Representatives. They led the way for countless women who now hold public office. In 1973 we held Credit Hearings at an open meeting at Dallas City Hall and invited women to tell their stories. One said she had been running the family business for two years when her husband succumbed to dementia but the bank would not give her a loan without his signature. Another said she had been supporting her aging parents for almost a decade; her mother had died and she needed a loan to buy a new car. The bank turned her down until she went to the nursing home and got her father’s signature on the application. A representative from Washington was there, and in 1974 the Equal Credit Opportunity Act was passed to prevent creditors to discriminate on the basis of sex, race, color, religion or marital status. Title IX passed as national legislation in 1972, but no changes were forthcoming in our school system. The most popular “sports” for girls were cheerleading and drill team, and there were no opportunities for girls to play soccer, basketball, volleyball, softball, etc. The Dallas schools were fighting Title IX, so I made an appointment at a Dallas Independent School District school board meeting. “As Women for Change members, and mothers, we would like ongoing sports for boys and girls open to anyone with interest and ability”. The chairman asked, “Are you saying a girl could play football?” I replied, “It’s possible, but not probable.” The chairman said, “Football pays for every sport, and they will never pay to see a woman sweat”. They all laugh, and I respond, “There has been recent legislation called Title IX which says no person on the basis of sex can be excluded from participating in an educational program or activity receiving federal funds”. They essentially dismissed me, so I thanked them and left. We immediately proceeded to file a lawsuit for non-compliance, and they were eventually forced to comply with the law. As needs surfaced and women stepped up to lead groups in which they were vitally interested, our nine task forces far outpaced our original goals. It is impossible to know how many different groups branched from the Women’s Center and/or we created the atmosphere in which they were accepted by the community. Here are a few: The Dallas chapter of the National Organization for Women; Women’s Equity Action League, The Dallas Women’s Political Caucus, Women’s Issues Network, The Rape Crisis Center, the Southwest Women’s Federal Credit Union, the Family Place, Dallas’ first shelter for victims of family abuse, the Dallas Women’s Foundation. I cherish the long parade of women leaders whose work made change possible, among them Virginia Whitehill, Vivian Castleberry, Joy Mankoff, Adlene Harrison, Victoria Downing, Kay Cole, Gerry Beer, Shirley Miller, Helen LaKelly Hunt, Becky Sykes, and Marjorie Schuchat. My personal role in this ever-growing, ever-changing revolution was all-consuming. I put in long days, sometimes as many as 12 hours, tending to our growing organization at the office and out in the community. I then went home to a constantly ringing telephone and listened as women’s hesitant voices spilled stories of neglect, poverty and abuse. I went to every task force meeting, both to support the leaders and to determine where there were duplications of service and/or voids in our projects. I did everything I could to be inclusive. We invited groups of to our monthly meetings—African American, Hispanic, Catholic Women, Church Women United, American Association of University Women, League of Women Voters—and we learned that while we can invite/include them, no group wanted to give up its autonomy. When we were charged with elitism—we were, middle class, educated white women—we had to admit that it was true, but we kept the welcome mat out to all. All of this had a price tag that our low membership dues could not support, so I became the chief fundraiser. It was in this capacity that I went to see Bette Graham, who as a former secretary had parlayed Liquid Paper, a product she created to paint over typing mistakes, into a multi-million dollar business. She and I shared many things. Both of us had been single mothers striving to support our sons; both of us were artists, she in painting and art collecting, and I in fashion design. She immediately understood what we were doing for women and provided funding for several Women’s Center innovations. One of my great disappointments was that her early death cut short our most ambitious project. We envisioned a women’s building and she had bought property and hired an architect to draw plans that included small shops on the first floor to provide income to support the building, meeting rooms on the second floor for non-profit groups and four small apartments on the top floor as temporary residences for single mothers struggling to find their way to independence. Sadly, this dream died with her in 1980 when she passed away at age 56 from untreated high blood pressure. Eight of us attended the first United Nations-sponsored International Women’s Year in Mexico City 1975 and came away impressed, inspired and ignited. I met educated, articulate women from all over the world who were facing the same problems in their countries. I became the North Texas advocate for the Women’s Agenda developed after the conference by Gloria Steinem and others. In 1978 we created the Women Helping Women Awards to honor those on the front lines of change. Eight years later the board approved an official name change to The Maura Awards for Women Helping Women in 1986. I am honored and humbled. This annual event is now sponsored by the Dallas Women’s Foundation, and draws up to a thousand guests every year.

In 1985, Helen LaKelly Hunt returned to Dallas to help a diverse group of us who were determined to create a foundation, with the goal “to be able to invest in longer-term programs that would facilitate systemic change”. The Foundation was built on the belief that when you invest in a woman, there is a ripple effect that benefits her family, her community, and her world. In the first decade, we awarded $3.5M in grants, and today the Dallas Women’s Foundation has granted more than $23M to over 1000 program benefitting more than 250,000 women and girls. Little did we “founding mothers” know that the Dallas Women’s Foundation would rank as the largest of the 160 women’s funds worldwide! For 30 years The Women’s Center changed lives, our own and the lives of others. By the end of the century, it became clear that we should no longer continue. Many of our original founders, including myself, had moved away from Dallas. Other organizations, several of which we had birthed, were doing the work we were founded to do, mostly better than we could because they were single-focused where we had been, as nearly as possible, all things to all women. By 2002, it was time to let go. We gifted our remaining most significant “projects” to other non-profits, emptied our offices, turned the key in its lock for the last time and walked away. We could declare victory through our many accomplishments. Backing up a bit, in1976 in the midst of all of the women’s center activities, came the worst tragedy in my life - the death of my precious daughter Andrea. She was born with a magic touch that enhanced the life of everyone she met. At 19, she was involved in a car accident that ended her life—and a large part of mine for a long time. There were years of grief and less energy for “causes” outside of my family life. Another tragedy that evolved more slowly – but has a happier ending - was the deterioration of my handsome, brilliant son. Rick was in graduate school when he began to hear voices that were not there. A friend suggested I phone Nancy Webster. Our first conversation was two hours. She became my tutor. I started going to a group whose members had a family member with mental illness. I listened and learned and read and became absorbed. My natural instincts for making change and advocating came back into use for this very difficult situation faced by so many. We learned how to bring comfort and courage and learned how to advocate for the mentally ill and their families. The silence regarding mental illness was deafening - I had lunch with over 15 different women who told me I was the first person they had ever told that a family member had a mental illness. It is a life long struggle for families. In 1989 we copyrighted a 221-page book – still useful – called A Helping Hand, “A Community, Media, and Legislators Resource Guide to the Mental Illness System in Dallas County Area”. We funded an emergency service van with trained personnel to be called by families in a crisis situation with their mentally ill family member. And we became one of the first official chapters of NAMI - National Alliance for the Mentally Ill - one of the most effective grass-roots organizations in the country. Much of this second wave of feminism described here happened over 30 years ago. So, what has happened in my own life since then? I gave myself permission to start over, just as I had long counseled other women to do. I got divorced; the marriage had disintegrated long before I took that step. And despite all that I had seen go wrong financially for women in divorce, I did not hire a lawyer and left the marriage with only my beloved Mercedes convertible and almost no other assets. I moved away from Dallas in 1990, and now live with my daughter Bridget and granddaughter Catalina in California. I could not have survived without her! I have been able to enjoy a great “retirement” – we live in a great house in Los Altos, and I don’t miss the crazy weather extremes in Texas or Minnesota. I have traveled extensively, have attended the Monterey Jazz festival for 20 years, and enjoy family life with my teenager granddaughter who is a delight in my life. My son, Rick, with great effort and determination, and no medication - has managed his life well. He lives alone in a house he bought in North Dallas, and when I go to visit him he treats me like a queen. He has supported himself doing long-distance hauling in a 1985 truck he bought. For 27 years he has traveled across the country averaging a million miles a year with no accidents. I am incredibly proud of him. I consider the Women’s Movement the most profound revolution in the history of our world and consider it an honor to have been a part of it. My gifts have been my stamina, resilience and flexibility, my openness to the strengths of others, and my Do It Now! Mantra. I think I have always recognized the interdependency of all life, and I agree (of course) with Hillary Clinton when she says, “Equal rights for women and girls are the “great unfinished business of the 21st century.” At 94, I am still passionate about women’s issues, and I am a forever feminist. And every spring I go back to Dallas to be a part of the Dallas Women’s Foundation Leadership Forum and Maura Women

|

Most, but not all, of us in the room knew each other. Thirteen were present. *Ginny Whitehill, the only one invited who was not able to come, was in New York at the bedside of her ailing father. The rest of us introduced ourselves and began sharing our life experiences. As powerful as it was to have found a safe place where we could share things that many of us had never voiced aloud, the meeting began to bog down. We could only so long indulge in self-revelations. The meeting’s purpose, as outlined ahead of time, was to find ways we could reduce the impediments that were holding us back. (pictured right: Ginny Whitehill and Maura)

Most, but not all, of us in the room knew each other. Thirteen were present. *Ginny Whitehill, the only one invited who was not able to come, was in New York at the bedside of her ailing father. The rest of us introduced ourselves and began sharing our life experiences. As powerful as it was to have found a safe place where we could share things that many of us had never voiced aloud, the meeting began to bog down. We could only so long indulge in self-revelations. The meeting’s purpose, as outlined ahead of time, was to find ways we could reduce the impediments that were holding us back. (pictured right: Ginny Whitehill and Maura) My father, an insurance man, provided our livelihood and my mother added the zest. We lived in Minneapolis, but had a cabin on Lake Pokegama in northern Minnesota, where we spent many summers. My mother loved getting to know the local Native American women and once exchanged some of her iron skillets for their hand-woven baskets. (pictured left: Maura playing in her favorite tree. Age 10)

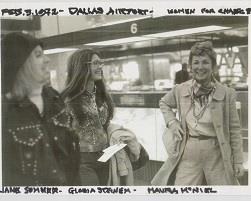

My father, an insurance man, provided our livelihood and my mother added the zest. We lived in Minneapolis, but had a cabin on Lake Pokegama in northern Minnesota, where we spent many summers. My mother loved getting to know the local Native American women and once exchanged some of her iron skillets for their hand-woven baskets. (pictured left: Maura playing in her favorite tree. Age 10) In 1972 we brought Gloria Steinem to Dallas and she packed the SMU Business School auditorium to capacity. Women students flooded in; when all of the seats were filled, some rimmed the stage for seating. Our membership exploded. Also, in 1972, I made 72 speeches to any group where I was invited—from AAUW to Zonta, lots of church groups, all-male groups, Rotary and Kiwanis, (at that time they had no female members.) With the help of volunteer office staff, I put out a monthly newsletter, wrote and printed a brochure, designed a logo. (pictured right: Gloria Steinem and Maura in Dallas, TX 1973)

In 1972 we brought Gloria Steinem to Dallas and she packed the SMU Business School auditorium to capacity. Women students flooded in; when all of the seats were filled, some rimmed the stage for seating. Our membership exploded. Also, in 1972, I made 72 speeches to any group where I was invited—from AAUW to Zonta, lots of church groups, all-male groups, Rotary and Kiwanis, (at that time they had no female members.) With the help of volunteer office staff, I put out a monthly newsletter, wrote and printed a brochure, designed a logo. (pictured right: Gloria Steinem and Maura in Dallas, TX 1973)