|

MAGGIE TRIPP - LIVING LEGEND, ACCIDENTAL FEMINIST,

WOMEN STUDIES TEACHER, WRITER, LECTURER

I was Born Female, but, of course,

I was not Born Feminist. I was Born Female, but, of course,

I was not Born Feminist.

Like other Philadelphia-born and bred girls, I expected to become a wife and mother; but, instinctively, I wanted

to explore what else I could be. And from childhood, I had a very independent mind. (In public school, my report

card was usually PP9. That's Poor for Conduct, Poor for Effort and "9" -- the best grade in the class.

( I was bored.)

The very idea of staying in Philadelphia for college drove me wild. I chose Barnard College in New York City; it

was the closest thing to a convent…one narrow bed, one dresser, a small desk and a set of rules on the back of

the door including front gates locked at nine p.m. to seal us from the men across the street at Columbia. I lasted

six weeks, then returned to Philadelphia, in time to make the January term at Penn. I went to Wisconsin and Cornell

for the next two summer sessions to catch up with my normal graduation date, the Class of '42.

But Penn didn't escape my boundary-breaking nature, either. Women in those days were automatically assigned to

Penn's College for Women. I wanted to learn about business. After a bit of a wrestling match with the powers that

used to be, I was admitted to classes at the Wharton School. As the only woman then at Wharton, I was called "ballsy

and aggressive," a title I publicly acknowledged years later when I was invited to return to Penn as the featured

speaker at the merger of the College for Women into the mainstream University of Pennsylvania.

Oh, yes, and did I mention I was married for a year and a half by graduation. time? It was obviously one of my

better decisions for we've now been wed more than seventy years. Alan has always helped me with my writing -- the

one thing I'll admit he does better than I do.

During World War II, I managed to have two children - Alan got home often - and took courses towards my Masters

in Art at Penn. But as soon as the war was over, I plunged into business ventures. Flowers-Every-Friday was a subscription

service. For three bucks a week, we'd deliver flowers of our choice to your house - the clever part was that we'd

go to the wholesale flower market at 5 a.m. and buy whatever was plentiful and cheap. The men who ran those wholesale

houses couldn't believe that two women (me and my partner, Doris Beifield) could sell and pay for so many flowers,

so it was all cash on the flower bed.

Tiring of rising at 5 a.m.. to deal with condescending men, I morphed to the art gallery business. Gallery 252

in center city Philadelphia was devoted to contemporary art and local artists, some quite excellent, though hardly

famous. I learned the truth about big time art when I took some paintings by best young artist to New York and

urged Leo Castelli, the dean of art dealers, to give this kid a break. Leo Castelli told me, "My dear, he's

quite good. But so are dozens of other young artists I've seen. And, you see, what my clients buy is my opinion

of my artists." I decided that, whatever I might do next, I wanted to be the arbiter.

Then, in 1966, to my surprise there came a request that moved my focus to academia. Ginny Henderson, the universally

respected Assistant Dean of the School of Women at Penn, called to say she had a grant from the Carnegie Foundation

to fund a course on "what women do with their lives." Ginny overcame my protestations of pedagogical

ignorance by putting me in a 30-day intensive training for teachers.

I taught that course, twice. What I saw was women wearing Peck & Peck suits who wanted to talk endlessly about

anything they might do -- but not really wanting to do anything. That was a clue. There was a lot of work to do

to change women's self-image.

That's when we moved to New York City. But I didn't leave Philadelphia far behind. Ginny Henderson and I conceived

and wrote a proposal for a book to show women how they could be in command of their lives. We titled it, "The

New Isabella." after the Spanish Queen who dominated her world. Dean Henderson sent me to the dean of literary

agents in New York, Carolyn Stagg, a wonderfully bright woman, then about 75 years old, who read the book proposal

and told me: "My dear, you're writing about quite modest goals for women. Go down to The New School in Greenwich

Village and catch up with the times."

And that's where feminism caught up with me.

I signed up at The New School for a class in women's rights. I was the only one in a dress, not jeans. The more

I listened, the more I knew how much I had been missing. It wasn't a question of fighting for an isolated justice

here or there. It was a movement, an uprising, a sea change in women's accepted roles.

To learn more about this new movement, I called the New York Women's Resource Center. I said to the woman who answered

the phone: "My name is Maggie Tripp and I've moved here from Philadelphia and I'm taking a class on Feminism

at the New School and I'm looking for more information on the subject." "Look," she said, "I

don't know what you're looking for but there are just two of us here. I'm Abortion and the only other one is Rape."

After a few months of investigating Feminism - with much more success than my first telephone call -- I told Ruth

Van Doren, head of the Women's Studies department at New School that I could teach a class called, "The Changing

Consciousness and Conscience of Women - Liberation How?"

Now the New School operates as a marketplace: people propose courses and, if the title and outline sound right,

the course gets listed in the New School catalog. Then, if enough people sign up to make the course profitable,

it gets a classroom and away you go. If not, you're cancelled. Well, women signed up in droves to find out how

to get liberated - and I figured out the lectures week-by-week.

"The Changing Consciousness…" lasted four semesters. As my own consciousness and horizons expanded, the

women's movement exploded and I was exposed to the minds of such socially intelligent people as Caroline Bird,

Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug,, Margaret Meade, Jesse Bernard and so many more great women. I expanded the feminist

premise with courses on small topics like "The Present and Future World of Women." When New York University,

New School's Greenwich Village neighbor, wanted to engage with the growing women's movement, they borrowed a group

of us from the New School to do a year-long series of seminars.

One fine day, Ruth Van Doren called

me and asked: "NOW wants someone to give a short talk to a meeting of the buyers for Federated Stores. Can

you do it? You know, tell 'em about how women and women's roles are changing. Of course, I said, "yes"

- without even asking what it would pay. (Turned out to be $50.) Then came the hard part. What do I say? What do

you tell a group of hard-nose retailers, mostly men, that they don't already know - something they'd accept --

about women? As always, I consulted my husband. He provided the winning opening lines: "Good morning, Buyers.

My subject today is how you can beat last year's numbers, week-by-week, month-by-month. Oh, and incidentally, I'm

going to mention a few things you may not know about how your women customers are changing." One fine day, Ruth Van Doren called

me and asked: "NOW wants someone to give a short talk to a meeting of the buyers for Federated Stores. Can

you do it? You know, tell 'em about how women and women's roles are changing. Of course, I said, "yes"

- without even asking what it would pay. (Turned out to be $50.) Then came the hard part. What do I say? What do

you tell a group of hard-nose retailers, mostly men, that they don't already know - something they'd accept --

about women? As always, I consulted my husband. He provided the winning opening lines: "Good morning, Buyers.

My subject today is how you can beat last year's numbers, week-by-week, month-by-month. Oh, and incidentally, I'm

going to mention a few things you may not know about how your women customers are changing."

Verbalizing my beliefs about free choice for women became a habit. And being at New School in the late Sixties

and Seventies was the right place to build a reputation. I became the Women's Studies Maven in Residence, being

quoted in newspapers and writing articles for magazines from the feminist journal, Aurora, to the plebian publication,

Modern Bride. In an interview, Long Island Newsday dubbed me, "The respected mouthpiece of the Women's Liberation

Movement."

Someone, I know not who, recommended me to Program Corporation of America, a leading Speakers Bureau and soon I

found myself delivering the feminist message to big gatherings of students at colleges across the country.

At Mt. Holyoke, it was "Money is as Beautiful as Roses." Wellesley got the message as "Legal Tender

Has No Gender." And in Green Bay, Wisconsin, albeit the home of the very masculine Green Bay Packers, they

really took the point when I said, "Take Charge of Your Life - and You'll Never Look Back in Anger."

By the mid-1970s, the world at large wanted to know about the feminist viewpoint. Program Corporation booked me

everywhere from Junior League meetings to the International Federation of Teachers and to self-improvement blow-outs

with Wayne Dyer. To my surprise, it paid well. But I also brought the message to women at the Lexington Avenue

YWCA in New York where lectures on women's changing role drew crowds and paid little.

Not all of the bookings were a pleasure. The prospect of freedom of choice for women worried some people, and no

one made a career of this fear more aggressively than Phyllis Schlafly. When Program Corporation asked me to debate

her in Kansas City on the Equal Rights Amendment, I leaped at the opportunity. Frankly, she dominated the debate.

But she had two things going for her. First, she stacked the audience with her followers who applauded on cue and

then seized the microphones for the Q. & A. Second, she tortured the truth, saying, in effect: "If you

get a job, your husband will leave you." But, afterwards, in radio interviews, I beat her because the men

who did the interviews gave me a clean shot at explaining what women really want. And the story in the next day's

Kansas City Star was more than kind to me and to feminism.

Nowadays, it seems everybody writes a book. But back in the 1970s, it wasn't so easy for an unknown author to find

a publisher.

I was blessed to know some authors in New York. Writer Leta Clark hooked me up with agent Elaine Markson who involved

Don Fine,, publisher of Arbor House Books, who loved my idea of asking each of the wonderful people who understood

feminism to write a chapter on how they foresaw women's lives.

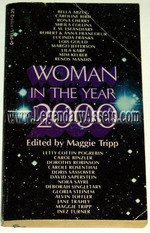

Who were the contributors? To name but a few, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Alvin Toffler, Margo Jefferson, Nora Sayre,

Lois Gould, and Lucinda Franks. The subjects ranged from women's impact on politics to a new balance of power in

business to equal joy in sexual relations. And, of course, the introduction plus a chapter called The Free Married

Woman plus editing it all were the work of one Maggie Tripp.

Don named the book, "Woman in the Year 2000." It was published in hardcover in 1974 and in paperback

in 1976. and 1978. And it's still around on Amazon.

Speaking of books, during my teaching years I had accumulated many hundreds of volumes about women and, when I

left New York in 1989, what was I to do with them? I had kept in close touch with Susan McGee Bailey and Jan Putnam

at the Wellesley Centers for Women who not only welcomed the gift but created the Maggie Tripp Library - which

I have happily supported ever since.

Besides teaching and writing I was on the Education Committee of NOW and active in the Political Caucus and represented

WEAL at the Houston, TX convention. And I always paid my dues to all those organizations -- until I just plain

retired. I am very pleased to be included in the encyclopedic volume, Feminists Who Changed America.

I'll celebrate my 91st birthday on July 7th. My husband is alive and well -- and writing this for me. I had two

children; my son's a musical electronics whiz and I lost my daughter to cancer two years ago. My three grandchildren

are, respectively, a male lawyer, a male engineer and a female doctor. My three great-grandchildren are two girls

and one boy who, no doubt, will grow up to benefit from my efforts to achieve sexual equality.

Comments to Jacqui Ceballos: jcvfa@aol.com

Back to VFA Fabulous Feminists

Table of Contents |

|