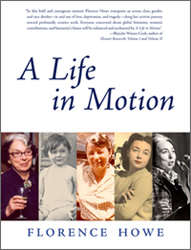

Florence Howe, feminist teacher, activist, editor, publisher, writer, a founder of women's

studies and the Feminist Press, and author of many books and essays, including A Life in Motion, a memoir. Florence Howe, feminist teacher, activist, editor, publisher, writer, a founder of women's

studies and the Feminist Press, and author of many books and essays, including A Life in Motion, a memoir.In the years before I was ten, my maternal grandparents-immigrants from Kiev (then Russia) and from Safed, Galilee-were as important to my life as my parents. Baba Sara loved me unconditionally and continued to nurse me through pneumonia when I was three, though the doctors and my mother assumed I would die. A few months later, after my brother's birth, I continued to spend most of my time with Baba Sara who taught me to knit, crochet, embroider, and for fun, play card games. She spoke only Yiddish and I learned her language at the same time I learned English. When she died suddenly in a bizarre accident, I was seven and I can still remember the day of that loss as though it were yesterday.

My mother had wanted to become a teacher but her father had allowed her only a high school commercial course, since he wanted her to marry one of the young rabbis he brought home to dinner. For five years after her high school graduation, she refused these rabbis, and then, at 21, Frances chose to marry Sam Rosenfeld, a man who had had no Hebrew education at all, nor more than six years of school. He was the son of a Polish immigrant who had entered the U.S. with her brother and year-old baby Sam. She worked at buttonholes, married again and was widowed shortly after she had borne two daughters. Thus, she depended on Sam who began working full-time in a house-furnishings shop before he was 12. My mother and father planned to make their fortune selling household goods, first from a pushcart, then from their own shop. Unfortunately, I was born in March 1929, nine months and a week after their wedding, which grandfather Max did not attend. Unfortunately also, the pushcart burned down and Sam began to support his family by driving a taxi. The first decade of their marriage and my life coincided with the Great Depression. Frances was not a happy stay-at-home mother, and I-plagued with colic-was not a happy baby. After my brother was born when I was three, my mother was fond of saying about her two children, "Isn't it a pity that he has all the looks and she has all the brains."

In January 1939, after my grandfather's death and just before my tenth birthday, my mother announced that she was going to work in an airplane factory and that I would do the housework and look after my brother. Fortunately, our move that year allowed me to attend a junior high school that happened to be a feeder school for the best high schools in the city. Two years later, an English teacher decided that I should be tutored in math so as to pass the test for Hunter College High School, thus setting me upon a path leading to Hunter College. Both institutions in different ways changed my life and career goals, though nothing could change the command my mother had given me when I first entered kindergarten: I was to become the teacher she had wanted to be. Hunter College High School assigned me to speech clinic, which forced middle-class speech into my mouth and traumatized me into silence at home and in the classroom. I studied full-time after school, even through my mother's radio programs and past normal bedtime, often still typing required history outlines when my taxi-driving father entered at two or three in the morning. Still, I could rarely earn the A's I was accustomed to. One high school teacher told me that I was the perfect B student, organized, diligent, reliable, and with not "a creative bone in my body." I accepted that assessment gratefully; in an alien world, I was pleased to be noticed. At Hunter College I regained my voice, if not in the classroom, then as a student activist, inspired by the college's motto: Mihi curae futuri-the care of the future is mine. Perhaps because the high school had been so demanding, at college I earned A grades easily and made friends as well. Our small group formed an inter-racial and inter-religious sorority, probably the first in the nation. In my junior year, when I was president of the Student Self Government Association, the dean of students saw me through the annulment of an unfortunate marriage. In that year also, the college president and another professor thought I should drop student teaching and prepare myself to become a college professor of English. Their letters sent me on to graduate school, overriding my mother's goals for me. A year later, M.A. from Smith College in hand, I entered the University of Wisconsin as a rare female teaching assistant. Still longing for motherhood, I also married a man working on his M.A. at the University of Chicago. Eventually, he transferred to Wisconsin to continue his graduate studies, but in the spring of what was my third year, he issued an ultimatum. I was to return to New York with him right then, or he would divorce me. I begged to be allowed to complete at least my residence requirements, but I did leave before writing my dissertation. Three years as a teaching assistant at the University of Wisconsin allowed me to gain an instructor's position at Long Island's Hofstra College in 1954. A year later, I reluctantly ended my second marriage, when it became clear that my husband would, under no conditions, agree to have a family. Two years later, in 1957, still chasing that family and the children I wanted, I married a psychologist on the Hofstra faculty. Surprisingly the nepotism rules that usually punished female academics were used against him, and I refused a tenure track, multi-year position.

We moved to Baltimore in 1957, where I could not find a teaching job, and instead decided to write my thesis and have a baby. Even with the aid of artificial insemination, I could not get pregnant or keep the fetus, and in 1960 gratefully accepted a temporary appointment at Goucher College, which turned into a tenured position as an assistant professor. Perhaps the teaching assuaged my desire for a family. Certainly, three years later, when my husband accepted a visiting appointment at Berkeley and wanted me to quit my job and come along with him, I realized that I couldn't do that. Had he been willing to adopt a child, had he been willing to deal with his need for alcohol, all might have been different. But I wouldn't leave the one part of life that satisfied me. So he went to Berkeley in August 1973 and I stayed in Baltimore, though we did not move to divorce until the following year, when I decided I was through with marriage forever. In the fall of 1963, students at the dinner table in the Goucher dorm where I often ate, asked me to drive them to a demonstration in front of a segregated movie theatre and barber shop near Morgan State College, attended chiefly by black students. After dropping my students, I worried about their safety, parked, and walked over to check on them. Thinking I was coming to join them, the students applauded and chanted, "Howe is coming." When I joined them, I didn't know that I would be ostracized by half the faculty for allegedly "leading students to break the law." The president of the college, hearing that I was sympathetic to the students' activism, assigned me to bail out students who were increasingly getting arrested as demonstrations grew larger and bolder all through Baltimore. In the early months of 1964, I heard about the organizing of Mississippi Freedom Summer, and in June the world learned about the murders of three young men who were attempting to register black voters. I went to Mississippi on a bus filled with people ten years my junior. In Jackson, I was assigned to open a school in the basement of the Blair Street Church, with six college students as staff. Among the 100 young people who turned up on the first day was Alice Jackson, a sixteen-year old who, the next summer, would come back with me to Baltimore as my adopted daughter. The immersion experience in Mississippi changed my life significantly. Henceforth, I would work actively to expose racism, and I would change my teaching methods. I learned to teach through asking "open" rather than "closed" questions in order to elicit responses from students who were learning to think about their lives and the social and political world around them. One question obsessed me: why could young black teenagers write better poems than my privileged white college students? I was going to change my teaching style in composition classes to elicit better writing. This sounds simple, and seems to have nothing to do with feminism. But, friends, this is how ultimately I became a feminist. One day, something happened in my Goucher College composition classroom while I was trying to teach young women to see that D. H. Lawrence's point of view in Sons and Lovers was never focused on the young women Paul Morel made love to. I asked students to imagine what might happen should Miriam tell her parents she was pregnant. "What would they have said to her?" No one responded. After some minutes of trying different questions, I grew impatient and fairly shouted, "O.K., what would your parents have said? How do your parents treat you, and how do they treat your brother?" Immediately, I had responses, and as we went around the room, students became more and more insistent that their parents treated them and their brothers equally. But when I asked more detailed questions about mowing lawns, washing dishes, hours, cars, allowances, and other matters, differences became visible, and the students tried to deal with them by claiming they would not want to mow lawns even if there was a payment, that they didn't need money, since their dates paid for them. I knew I was on to something when students groaned as I assigned this as a writing topic. I had found a topic that young women in the mid-sixties could write about, and I began to call my course "Identity and Expression." Only in 1969, when the women's movement hit U.S. campuses, did my composition course become popular. That same year, when students asked why there were no women writers in the eighteenth century course I taught, I had to admit that I knew of none, that I had studied only men. And again, I knew something was wrong. Other key events pushed me into feminism in 1969 and 1970 and led me to women's studies and the founding of the Feminist Press. The newly-founded Chronicle of Higher Education sent a reporter to my composition class who then put my picture on its front page, claiming I was "teaching consciousness," even though I insisted I was teaching composition. The Modern Language Association appointed me as the first Chair of its newly-founded Commission on the Status and Education of Women in the Profession, and asked that I prepare a study of the status of women in 5,000 English and Modern Language Departments. My report found that women were 80 percent of those studying English and the modern languages, but they were only 20 percent of those applying to doctoral programs. The study made clear that women with high grades chose not to apply to doctoral programs, leaving the field open to men with weaker grades. How could this be? What discouraged women from even applying? The short answer was, of course, the male curriculum, which, when it included women at all, derided or sexualized them.

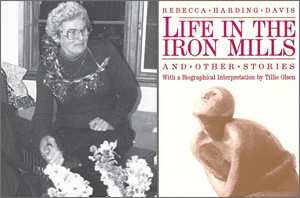

Early in 1970, three university presses asked me to write a biography of Doris Lessing. I told them I wanted to begin another project: a series of 100 short biographies about dead women, to be written by living ones, including Doris Lessing. All turned me down, saying "there's no money in it." In July members of Baltimore Women's Liberation, who said they had no time to work on a project that might be called the Feminist Press, nevertheless, without telling me, announced its existence. When I returned from a month at Cape Cod, I found more than a hundred letters, some with checks and bills, in my street mailbox, addressed to The Feminist Press. The letters indicated that Baltimore Women's Liberation had also announced that the Feminist Press would publish children's books as well as the biographies I had suggested. Fifty people attended the first meeting of the Feminist Press in my living room on November 17, 1970. A few months later, Tillie Olsen sent me a copy of Life in the Iron Mills, a novella first published anonymously in the Atlantic at the request of its author in 1861. Tillie now knew that its author was a woman and she wanted the Feminist Press to publish it. Reading it, I knew that if such a masterpiece had been "lost" for more than a hundred years, then much more must also be lost. So, in addition to biographies of women and feminist children's books, we began to publish "reprints" of important women writers, a series that has continued as a mainstay of the Feminist Press. Some of these women are household names today: Rebecca Harding Davis, Zora Neale Hurston, Paule Marshall, Louise Meriwether, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Frances Harper, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Kate Chopin, Agnes Smedley, Mary Austin, Edith Summers Kelley, Tess Slesinger, Myra Page, Helen R. Hull, Fielding Burke, Meridel Le Sueur, Margery Latimer, and others. These books have changed the curriculum in literature and history both at the high school and college levels, and, I am certain, have also been responsible for the fact that the majority of doctoral candidates in English and the foreign languages are now women. Less than six months after the Feminist Press was founded in Baltimore, I moved, as professor of American Studies and Women's Studies, to the College at Old Westbury, a new SUNY campus on Long Island. The Feminist Press moved with me, where it was given generous quarters at the College and eventually a small two-family house of its own on the fringes of the campus. Surviving a fire in 1983, we moved into a formal association with the City University of New York in 1985, where I was appointed full professor and released from teaching to run the Feminist Press. In 2000 I retired as publisher/director, and in 2005 returned while the Board of Directors searched for a new director. When Gloria Jacobs was appointed in early 2006, she asked me to stay on as publisher for two years. I retired once again in June 2008, when I began to write my memoir full-time. A Life in Motion was published in 2011 by the Feminist Press.  The memoir, A Life in Motion, contains chapters about my early life, education, and four marriages, as well as my father's

and brother's suicides, my mother's decade-long siege of Alzheimer's, and, on happier notes, my friendships, and

my life as "another kind of mother." I have two non-biological families, one black, the other white,

and they know and care about each other. While all this would have been enough for a single volume, I had another

goal: to write a history of the first 38 years of the Feminist

Press. During those same years,

I was also an advocate for women's studies a new multi-cultural, interdisciplinary explosion of the curriculum

attempting to uncover the lost history, literature, culture, and lives of women, and through that process re-vision

the world that male culture had created. Not surprisingly, I once described the relationship between the Feminist

Press and women's studies as symbiotic, meaning that women's studies needed the books that Feminist Press was producing,

and Feminist Press needed women's studies as a natural market for its books. Thus I spent much of the 1970s and

1980s on the road, a tireless advocate for women's studies, and at the same time, a promoter of the new-found literature

by and about women. The memoir, A Life in Motion, contains chapters about my early life, education, and four marriages, as well as my father's

and brother's suicides, my mother's decade-long siege of Alzheimer's, and, on happier notes, my friendships, and

my life as "another kind of mother." I have two non-biological families, one black, the other white,

and they know and care about each other. While all this would have been enough for a single volume, I had another

goal: to write a history of the first 38 years of the Feminist

Press. During those same years,

I was also an advocate for women's studies a new multi-cultural, interdisciplinary explosion of the curriculum

attempting to uncover the lost history, literature, culture, and lives of women, and through that process re-vision

the world that male culture had created. Not surprisingly, I once described the relationship between the Feminist

Press and women's studies as symbiotic, meaning that women's studies needed the books that Feminist Press was producing,

and Feminist Press needed women's studies as a natural market for its books. Thus I spent much of the 1970s and

1980s on the road, a tireless advocate for women's studies, and at the same time, a promoter of the new-found literature

by and about women.Although I had spent three weeks in China (as a "feminist") and three in India (as a women's studies founder) during the mid-1970s, after January 1980, the focus of my work in women's studies and in feminist publishing became increasingly international. Early in 1980, Mariam Chamberlain, a program officer at the Ford Foundation, appointed me her advisor on a three-week tour of women's studies in Europe, an event that marked the beginning of two decades of international work that she, the Feminist Press, and I did for women's studies. Much of this came through United Nations meetings in Copenhagen (1980), Nairobi (1985), and Beijing (1995). In each case, the Feminist Press had Ford grants and sometimes UN funds as well to invite scholars to attend the Forums and to report on the development of women's studies in their countries. Thanks to such financial support, some hundred reports were published and circulated to scholars world-wide through our own Women's Studies Quarterly. Mariam and I also attended and often spoke at other international meetings in Canada, Costa Rica, Ireland, Australia, Uganda, and New York. Through the 1980s and the 1990s I continued to speak on the international development of women's studies both at international conferences in Korea, Italy, France, Poland, Japan, Germany, India, and Argentina. In 1983, on a lecture tour in India, I found Susie Tharu, a professor of English literature in Hyderabad, who became one of the editors of Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the Present, ultimately published in two huge volumes by the Feminist Press in 1991 and 1993. Reviewing these volumes, notable critics have claimed that their contents had markedly changed the history of India. Today many of the 140 writers have volumes of their own, and young Indian female authors know that they have a long history of other women writers behind them. Early in the 1990s, the Indian volumes were seized upon by African scholars in the U.S. who wanted to produce similar volumes for their continent, and fifteen years later, the Feminist Press completed the publishing of Women Writing Africa in four regional volumes-South, West/Sahel, East, and North. All of these volumes will shortly also be available in French.

Beginning in 1996, I traveled often to some ten African countries, for multiple meetings with African scholars, writers, translators and editors, gathering and preparing texts for these volumes. In addition, when their volumes were nearing completion, all of us-African and American editors traveled to Bellagio, Italy, to work on team residencies at the Rockefeller Foundation's Villa Serbelloni. I close the memoir in several ways, hearkening to the oft-cited wisdom that humans, whether female or male, need both love and work, and defining love as emanating from deep friendships. I describe my New York "family of choice," all of whom, have become acquainted with my non-biological families, now scattered through the U.S., from California to Mississippi, Kansas, Illinois, Connecticut, and Washington, D.C. And I describe the providence of two personal Bellagio awards from the Rockefeller Foundation that allowed me to write the memoir, and six team awards to Women Writing Africa that allowed the completion of that project. What I don't say is what I could not have imagined during the intense two years of writing and rewriting the memoir itself: how difficult it would be to "retire," not only from managing the Feminist Press, but especially from working on the Women Writing Africa project, which kept me in motion through 2009. What I understand now is that my life in motion was not simply the experience of being in planes, trains, and other moving vehicles, but the emotion of working with other people. At least so far, I haven't found any way to recreate that experience in retirement. To buy A Life in Motion, please visit: feministpress.org. To visit my website and blog, please visit: florencehowe.com. Contact Florence Howe: FLORENCH@aol.com Back to Table of Contents |