|

REBECCA LUBETKIN - POLITICAL SCIENTIST, NOW

ACTIVIST, HOST OF TELEVISION SHOW "NEW DIRECTIONS FOR WOMEN" NOW Keynote Speaker 1991

It is not so surprising that I was not aware of sexism. If anything, in my family females seemed privileged: my brother did not have a better deal than his sisters; my mother was well educated, more so than my father; my father was willing to leave college to put his sister through medical school. With that background, I did not notice the many gender inequities the world doled out. But I am sure that my early experiences sensitized me to issues of injustice and thus played a part in preparing me for my future activism. I graduated in 1960 from Barnard (Columbia University), a women’s college where women’s education and futures were taken seriously and where no pursuit was seen as inappropriate for women. In fact I did my graduate work in political science (then considered a male pursuit), and later worked as an instructor of public policy at Rutgers, when Rutgers College was still all male.

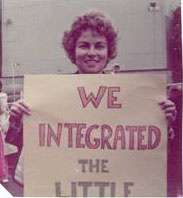

I met my husband, Daniel Lubetkin, when he was a member of the State Legislature. I was part of a team of Rutgers academics that had been requested by the Legislature to conduct an analysis of its procedures with the objective of proposing recommendations to improve the legislative process. Daniel, a lawyer, was one of the legislators I interviewed for this study. We married in 1963, and gave birth to two daughters in 1967 and 1968. One great influence on me was that in my early years I had been raised by paid help; I determined early that, when I gave birth, no activity outside of the home would be more important or have higher stakes or be more worthy of my devotion than the rearing of our future children. And so Dan and I embarked on a very traditional marriage; he was the sole earner and I was the caregiver. By the late 60s, when our daughters were 2 and 1, I had heard of the beginnings of the women’s liberation movement. But I discounted it, telling myself that “women’s lib” may be needed by some, especially those who personally suffered from a big, bad father or husband, but I did not fit into that category and so didn’t need it. Then one day in 1970 I was reading an article in the Barnard Alumnae magazine about the new movement that referred the reader to a list of recommended readings. I read Black Like Me, and it changed my life!! The author, John Howard Griffin, a white Texan, had traveled by bus through the racially segregated south as a Black man, and described the differential treatment he received, even from unknowing acquaintances, based only on skin color. I likened sexism to racism, realizing, for the first time, that sexism is not just personal; it is also social, cultural, political—transcending one’s individual circumstances. Things changed quickly. I was still a full-time child-rearer/homemaker (for the next five years), but joined a consciousness-raising group with diverse members. (That group was supposed to end after 10 sessions, but actually continued for 30 years!!) I joined NOW in 1971 and began to see limitations based on gender around every corner—in our daughters’ preschool and elementary school, in their organized, recreational activities, in athletics—a girl could not be captain of the safety patrol, could not ride a bike to school, could not play recreational soccer or basketball, could not play kickball with the boys at lunch, but had to remain on the blacktop. Books had mostly boys as main characters, and there were almost no biographies of women in the school library. In classrooms teachers focused on the boys, called on them more often, and asked them more probing questions. There was lots more. While I worked on many issues, my main focus was on schools. I was chair of NOW-NJ’s Task Force on Education when we filed hundreds of separate formal Complaints with the New Jersey Division on Civil Rights contesting the practice of requiring middle school girls to take home economics and boys to take shop (and for the most part not allowing cross-gender enrollment). We won and seemingly overnight, schools opened all courses to both sexes. There were many struggles and triumphs, local, state and national. Most changes are taken for granted now, but in the 70s generated strong opposition and even mockery; for instance:

And then in 1975, Rutgers University asked me to write a grant proposal to support training for educators in how to achieve equal opportunity. That proposal was funded, and resulted in the creation of the Consortium for Educational Equity, and I was hired as executive director at the rank of assistant professor. For the next 25 years the Consortium provided leadership to schools in making the changes needed to transform the educational practices and programs to provide equitable education opportunities. Originally targeting schools in New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, and only gender bias, the work was later expanded, through successful competitive funding applications, to reach much of the country as well as to include policies and practices that limited students based on race and national origin as well. I also served as Associate Director for Equity of the Rutgers Center for Mathematics, Science, and Computer Education. By the year 2000 I had advanced to full professor and finally, with my retirement, to emerita professor. I am the author, editor, or publisher of numerous books and articles and videos. Among them were the earliest policy and practices manuals for restructuring educational programs to provide equal opportunity. These include pioneering (1976-79) guidelines for developing equitable opportunities in athletics as well as curriculum guides in social studies, language arts, and the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields. We also designed and conducted scores of Futures Unlimited conferences at local colleges to interest girls in pursuing careers in STEM fields. We assembled in our library the largest collection in the country of multimedia resources in educational equity.

What made it all possible was Dan’s extraordinary support as I moved into employment. Clearly I was changing the rules that had structured our lives from the beginning when, inspired by the feminist movement, I applied for and was offered that assistant professorship in a field that did not exist and which I would have the good fortune to define myself. It was an opportunity afforded to few—to be able to pursue my feminist passion and to be paid for it. We both knew I could not accept without substantial changes at home. I had to give up my determination to avoid paid child care help. After-school care in those days was available only in poor neighborhoods. Not only would we need a housekeeper (the children were then 8 and 7), but Dan would have to do many of the tasks only a parent can do. The inconvenience and radical intrusions on his time would in no way be compensated by my very low academic salary. He sacrificed many of his own professional and personal goals to accommodate our family’s new needs, making it possible for me to take a job 35 miles away that required my absenting myself from home from 7:30 am to 6:00 pm daily. We have been married for 48 years, our daughters are grown, each married with two children. Julie Lubetkin lives in San Carlos, CA, and Dr. Erica Lubetkin lives in Manhattan. I have been retired for 11 years, although I have continued to work part-time as a consultant at Rutgers. Since retirement, I have been an activist primarily in international women’s rights: my causes have been genocide, rape as a weapon of war, slavery, honor killing and sex trafficking. These activities include writing, demonstrating, political organizing, lobbying, and canvassing. I was also involved in the anti-war movement as an active member of the Raging Granny Brigade, protesting the Iraqi War in various places including the Times Square Armed Forces Recruiting Station. I'm a member of VFA's Board and among my other current volunteer activities is involvement since 1993 as part of the production team for the television show, “New Directions for Women,” produced by the Morris County chapter of NOW through CableVision and aired in many outlets of the country. I became host of the show in 2007. More than 200 shows have been produced, and all are archived in the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College; most shows are available on youtube at www.youtube.com/mcnownj Contact Rebecca: lubetkin@rci.rutgers.edu COMMENTS: Jacqui Ceballos jcvfa@aol.com |