BONNIE ATWOOD - EARLY WOMEN'S LIBERATIONIST, LAWYER,

WRITER  I was born Bonnie Atwood

and grew up just about five miles from Washington, D.C., in Arlington, Virginia. It was 1947, in the suburbs—the

new place for families. Our little community had lots of children my age. We had bikes, and roller skates, and

a movie theater, and a big wooded area where we could play Davy Crockett as long as we wanted. I was born Bonnie Atwood

and grew up just about five miles from Washington, D.C., in Arlington, Virginia. It was 1947, in the suburbs—the

new place for families. Our little community had lots of children my age. We had bikes, and roller skates, and

a movie theater, and a big wooded area where we could play Davy Crockett as long as we wanted.Fathers went off to Washington to do government work. Most mothers stayed home and baked and sewed. My father was a cabinetmaker. My mother was one of the only ones who went to Washington every day and worked at a government job, first as a stenographer, and then as a customs clerk. It was fairly low level, but she seemed to like it. She had grown up in a very poor family, and all the women and men always had jobs. I think we needed the money, but I also know that it was important to her to have her own paycheck, and not go to my father for money. My mother was very proud and independent, and she instilled that in me. The very unfortunate dark side of this was that for most of my tender years, I had to spend every day in demoralizing childcare situations. I liked playing with the other children, but the adults (with some exceptions) around me were cold toward me. My mother would wake me very early in the morning, and then take me to the sitter. One of my sitters made me just sit on the couch while her children slept late in the mornings. I always sensed that she didn’t want me there at all. The babysitters didn’t mean to do this, but they always made me aware that I wasn’t one of their own golden babies. They would say to other friends they met, “These are my children, but this one’s not mine; she’s the little girl that I keep.” I’ve always been good at making friends, but in this sense, I always felt like the outsider. And it was never a secret that they kept me because they received money for my care, and that they sometimes asked my mother for pay raises. I never discussed this with my parents, whom I loved, and I doubt anybody ever thought about it, but the concept felt hurtful to me. I may have been unusually sensitive to this, but I have heard a few people speak of it. I had no words for it at the time, but I felt that my very survival required figuring out what my paid sitters wanted me to do, and quietly walking on eggshells so as not to be more burdensome to them.

It changed who I was. I think in the long run, it gave me strength, and laid the groundwork for my strong advocacy for housewives (this is my preferred term), for welfare mothers, for military wives, and displaced homemakers of all kinds—women who commit themselves to family and who want to spend their days with their children, and be respected for it. I am always looking for ways that they can be validated, both financially and emotionally. I also have a special empathy for women who have been marginalized, and even abused, by their religions. It distresses me that often feminism has been perceived as neglecting family caregivers in favor of career women. I became involved and committed to the feminist movement when I was a Psychology student at George Mason University (then George Mason College) in Northern Virginia in late 1960s. I remember vividly my first encounter with the Women’s Movement. I was already deeply involved with the Peace Movement and Civil Rights issues. I read an announcement in an alternative newspaper of a meeting for the first class for what was then called “Women’s Liberation” to be held at the Institute for Policy Studies, a kind of New Left think-tank, off of Dupont Circle in nearby Washington, D.C. IPS is still going strong. The short ad said something about the women in the Peace Movement getting fed up with how men were treating them as second-class. I spoke with my two closet friends, both women, and we all said, “Yes! We’ve got to be there!” We met on the second floor of the old IPS townhouse building. I will never forget the wonderful feeling and the beautiful women who attended. I even remember the first night, and our entrance to the room. We were struck by how they referred to us as “women,” not “girls.” We asked them about that. They said, “we would never call someone a ‘girl’ if she were over age 12 or so.” We sat around a table. The women sat with their legs every which way, not caring about the old rules about being “ladylike.” We found articulation of thoughts that had been trying to get out of us for a long time. It was a life-changing moment. My life was never the same after that. The group continued meeting there very often, and developed a large and solid, if informal, following. When the class was over, we still met as “Washington Women’s Liberation.” Then there were spin-off groups: Off Our Backs, The Furies, The Witches, etc. We met, we talked, we read, we demonstrated, we made movies, we wrote articles. We had consciousness-raising groups. We had health information sessions. We formed classes to teach ourselves car repair, labor history, the history of the Suffrage Movement, women’s fiction--just everything. It was exhilarating. We designed a whole new world. Feminism quickly became the most important voice of my life. It still is. I dropped out of college for a while, and lived in Washington, where I was very active. We lived in communes, so we didn’t require much money. We had one little stereo record player. Our entertainment was free concerts in the park. The last thing we cared about was climbing a corporate ladder. I worked part-time at a couple of bookstores, taught ice skating lessons, worked as a payroll clerk, and as a “hatcheck” girl at some very fancy D.C. restaurants.

Eventually, I went back to school, uniting there with students and professors who were just starting important activities there, later to evolve into formal Women’s Studies programs. I went on to graduate from GMU. My degree was in Psychology, but my interest was in journalism. I got a job on the staff of a daily newspaper in Northern Virginia. I loved that experience, and I worked there for four years, with much happiness and success. At that point, I married, and had a baby. I dropped out of the labor force for a while, but later I did freelance writing from home, while my baby slept. Our little family moved to my current home in Richmond, Va. I was very focused on home and family, with writing on the side, when, to my surprise, my divorce occurred, after ten years of marriage. It was devastating. I cannot even describe how I felt, and I really didn’t have time to feel. I had to suddenly find a higher paying job, get after-school care for my child, and get my life in order in a way that I had never anticipated. I felt like I was scotch-taping a broken life back together. I worked as a rehabilitation counselor for the next few years, but I knew I would have to find something more substantial.

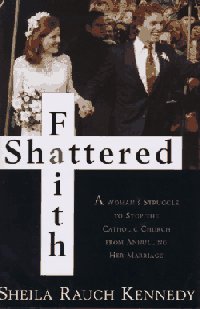

I became magazine writer, too, using my writing to discuss feminism as much as I possibly could. Life since my divorce has been a struggle. Marriage, motherhood, divorce, and eldercare drove home what I and many other feminists have found: that autonomy is a myth. In my forties, somehow, with the support of friends, and a couple of years of trying, and lots of financial aid, I went to law school at the T.C. Williams School of Law at the University of Richmond. It was a tough three years, but I loved it. I graduated, but I am not a practicing lawyer. I got interested in professional lobbying, advocating for groups instead of individuals. I am currently active in an international initiative to recognize caregiving work. The group plans to launch a petition to support two Congressional bills (H.R. 4379 and H.R. 3573, which would make changes in the current welfare laws. Look for more information to come this fall. I write about feminism as much as I can. I believe my most significant contribution to the Women’s Movement has been my opposition to the Catholic annulment system. Most church officials will deny it, but my experience is that thousands of former spouses, most of them women, have been severely hurt by the annulment process. I am not, nor was ever a Catholic, but am interested because many non-Catholics are also affected by this outrageous “law”. As much as I respect the Church in many other ways, I am alarmed at what I have seen it do to divorced wives and husbands and their extended families, mostly in the United States and Canada. The strange, lengthy process is carried out in private, and it breaks down families in irreparable ways. I network with women who have experienced this and feel as I do. I see my work in this area as my most important feminist activity. (For more information on all this, go to www.saveoursacrament.org. I work now as a professional lobbyist, representing such groups as the Virginia Retired Teachers Association, and the Virginia Association for Marriage and Family Therapy. I started my own writing business, Tall Poppies Freelance Writing LLC, in 2008. I am currently active in an international initiative to recognize caregiving work. The group plans to launch a petition to support two Congressional bills (H.R. 4379 and H.R. 3573), which would make changes in the current welfare laws. Look for more information to come this fall. I’m very proud to call myself a veteran feminist. Contact Bonnie: bonatwood@verizon.net Comments: jcvfa@aol.com Back VFA FrontPage |